Biomimicry in architecture

October 5, 2016

In Folk Hall Auditorium, a crowd of students, faculty, and community members gathered to attend Philip Beesley’s lecture on the uses of robotics and artificial intelligence in architecture, Monday evening.

Beesley is a visiting professor in architecture from The University of Waterloo and professor of digital design and architecture & urbanism at the European Graduate School. He will perform a residency at UA’s school of art in the spring semester of 2017, where he will teach a class and produce work with the students.

He was invited Monday evening to introduce himself and his work, which strives to elicit a new, curious sense of public space and architecture.

The auditorium was packed to capacity and more. As the lights dimmed, UA graphic design professor Marcus Vogl introduced Beesley.

Tony Samangy, associate professor, attended a lecture of Beesley’s at a past conference on computer graphics. They have remained in contact ever since, laying the groundwork for his arrival at Myers.

The lecture began with an introduction of Beesley’s previous work and prevalence in journals and publications such as MIT’s Technology Review.

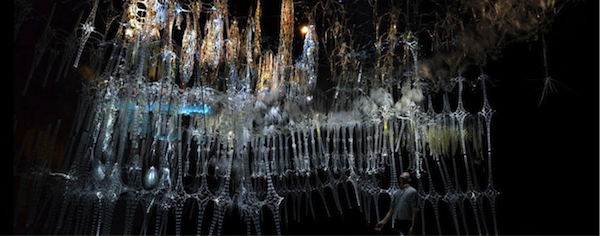

Against a large, white wall, a projector displayed internationally displayed works and installations of Beesley’s projects. The systems shown were enormously complex environments assembled from man-made materials (inorganic) that spanned and illuminated vast chambers of darkness.

After viewing several installations, Beesley told the audience how the framework unifies the installations and acts as a means to transfer motion and stimuli.

Beesley showed several examples of scaffolding components that form the skeleton and link to the exposed exterior. Small servos, motors, and linkages actuate the components, which are made from polymer, glass, and metal.

The mechanisms in the sculptures also react to human presence, which gives the structure the sense of being a living environment. Some systems, when a disturbance is identified, will try to further detect and seek out movement by repositioning themselves.

Shape memory allows a component to detect approaching visitors in the environment, which triggers responses such as dynamic lighting and further ripples of motion.

A large amount of engineering and design work goes into each system and its components.

The environments are an exercise in biomimicry: they appear as organic and sentient, but the artificial intelligence of the systems moves through its electronic controls. Other systems feature fluid movement via insoluble combinations of oil and water.

Jillian Olson, a mechanical engineering major, compared the environment’s behavior to that of a circulatory system.

Beesley explained his work is “not a proud architecture, not unified.” It has a weakness and fragility that seeks maximum exposure to the outside world.

To produce this exposure, the environment interacts with its occupants. The vulnerability generated by this, Beesley argues, contradicts human nature to seal off the outside world with decisive permanency.

However, the work is not without its challenges or unexpected discoveries. Beesley described a system that’s intent was to be receptive to slow human movements and shun fast movements.

Ultimately, the system behaved differently than anticipated and showed a sustained trembling that was independent of human input. But Beesley is undeterred: “Potent discoveries [are] to be made”.

Several couture exhibits were shown where Beesley had adapted his work for apparel. The clothing mirrored the works of his installations. Dresses, blouses, and other pieces featured numerous delicate fronds and rippling geometric patterns.

The clothing is challenging to wear and, Beesley admitted, “some pieces are un-sittable.” But the notion of maximized exposure was prevalent in the apparel.

Concluding his discussion, Beesley argued that the work is naturally resilient, both adaptable and sustainable in quality. He hopes that his lecture engages people’s curiosity to ponder a world where the architecture is inviting, and seeks and responds to one’s presence.

A brief question and answer session followed the lecture, in which the patent benefit and societal contribution of Beesley’s work were examined. Beesley adroitly defended his work, arguing that it necessarily produces answers and questions that are worth exploring and provides meaningful dialogue between man and his environment.

His response drew applause from many in the audience.

David Patterson, a retired community member, who has worked at the Cleveland Museum of Art, reflected Beesley’s sentiment, contending that, “art supplies a multiplicity of answers for questions unknown [or unasked].”

The residency program is made possible by the Mary Schiller Myers School of Art. Beesley’s lecture was part of the “Collider” series of exhibitions and lectures.

The lecture was made possible by Synapse, an interdisciplinary group that fosters collaboration and innovation between art and science.

For those further interested in Beesley’s work, please visit philipbeesleyarchitect.com.