Do You Want One?

November 6, 2018

I know it is coming. All the signs are there, all the warning bells and flashing claxons: “WARNING! WARNING! PREPARE FOR IMPACT!” I feel my gut clench and my palms start to sweat, and I wipe them preemptively on my jeans, hoping no one will notice the awkward movement. I’m no stranger to this chain of events; without fail, it has ended the same way: panic, disaster, disappointment. There is no winning this battle, nor is there hope of escape. I brace for the blow as my friend Rachel turns from her scavenging in the pantry, clutching the payload in its plastic clamshell, and locks onto her target. She moves in for the kill. (I reconsider the possibility of escape: I might be able to break a window, and this apartment she shares with my girlfriend is only on the first floor.) Her face neutrally friendly, she plops next to me on the cheap leather couch and waggles the miniature cupcakes under my nose, the scent of whipped shortening and shame wafting up to me. She deploys the ordinance.

“Do you want one?”

I was maybe five years old, sitting at the counter in my aunt’s new house. She and her husband built it: the pinnacle of southern suburbia. The house was of moderate size, built into the side of a hill; you could climb three stairs to walk through the front door and then need a ladder to climb from the back porch to the ground. My aunt was a middle-school art teacher, and it showed; the blues of the vinyl siding and of the giant porch complemented each other with color-wheel precision, and the scheme was subtly echoed throughout the interior, down even to the appliances. The kitchen opened onto the living room, which was positively cavernous. As I sat, munching on the tray of veggies (I’d heard them called croody-tays?) my aunt had set out, I felt my gaze drawn up and up and up, the white walls in this room compounding its cathedral-like enormity. Through the glass back door, I could see the enormous backyard as it sloped surely but gently down for what seemed like miles, the pastoral strait is broken finally, way off in the distance, by the leg of I-77 that runs through the tip of North Carolina. To my eyes, accustomed as they were only to suburban Cleveland, it was fearfully exotic—novel and exciting, but most certainly not my home.

I spun on the stool where I was perched, checking in on my mom and her sister. There they still were, my mom’s brunette perm in stark contrast with my aunt’s bushy reddish-brownish hair. They were gibbering about some or other of those boring but presumably important topics only adults could understand, but I didn’t mind; I was content peering around this humongous space, noting how different it was from my own house. Doodads were scattered about, each displaying the personality of my aunt and uncle. This fascinated me. It had never occurred to me that other people’s homes would be different, that they would have unique layouts and knickknacks, or that they would so closely mirror the people inside. The house was spotless, and the furniture and décor had been arranged with great precision and perfect angles. In one corner was my uncle’s shrine to golf: a breakfront against the wall holding golf books, golf pictures, golf tees, the three-foot vase full of golf balls. The whole house felt like a museum, which made perfect sense to me—my aunt taught art to big kids, and art goes in museums, so it followed neatly that her house would be a museum.

Satisfied with my reasoning, I picked up another piece of broccoli. I knew what to do, of course. Back home, my mom would sometimes take me to the corner deli, Martin’s, in the next suburb over, where I was mesmerized by the strange and bizarre foods on display. Who knew that you could buy eggs already hard-boiled or canisters of potato sticks? And I knew kids weren’t supposed to like broccoli, but I’d found a way around that. See, when you bought broccoli, I had discovered, the little trees would be in a plastic tray, situated around a cup of this stuff my mom said was called “ranch,” which confused me since I thought ranches were where horses lived. Nomenclatural conundrums aside, this ranch stuff was great! The broccoli made an excellent ranch delivery device: dipping the little buds in the goo and then licking it off was quite efficient, and then you could go right back in for more—no waste! I did know, kind of, that this was cheating and you were supposed to actually eat the green part, but my mom never objected, so I figured it couldn’t be too egregious.

My aunt noticed as, for the third time, I dove into the dressing in the middle of the platter. “What are you doing?” she shrieked, zooming across the kitchen from her conversation with my mom to snatch the plate away. “That’s quite enough, William.”

I gaped at her, stunned. What had upset her? My parents entertained frequently, and the procedure was clear: small foods were put on big plates and everyone helped themselves because that’s how it worked. Now here in front of me had been a selection of small foods on a big plate, and I had followed the script. What had I done wrong?

My aunt turned to my mother with annoyance on her face. “He’s eating my lunch!” she complained. “I could understand one or two, but he was double-dipping, too!”

“William, that’s not polite,” my mom said slowly and melodically, each syllable pronounced clearly and individually. “We don’t help ourselves to other people’s lunches. And we only dip once.”

I sat frozen, my mind tumbling with so many revelations at once. Lunch? What lunch? Vegetables? What kind of lunch was a tray of vegetables? A selection of vegetables was the kind of thing you put out on big plates for people to take—not lunch. (Lunch was sandwiches—everyone knew that.) And what in the world was “double-dipping”? If something were wrong with my dipping practices, why hadn’t my mom said something one of the countless times we’d gone to Martin’s? And most of all, why couldn’t my aunt have just asked me not to eat anymore? Why did she look to my mom to intervene as though I’d misbehaved?

I was startled and scared and guilty, acutely aware that I had waltzed merrily across a glaring red line that it seemed everybody could see, except for me.

After the grown-ups returned to their conversation, I silently hopped down from the stool and slunk across the hardwood floor to the corner of the kitchen. I tossed the piece of broccoli into the trash.

By the February of my junior year of high school, Audra and I had been dating for a few months, and I had become comfortable—or, at least, no longer felt unbearably out of place—spending time at her house in the afternoons. While her mother’s boisterous intensity (and giant black hairdo) never failed to put me on edge, the woman had certainly never made me feel unwelcome. She would often come home to find Audra and me lazing on the couch, staring at some meaningless nonsense on TV, and once in a while, I would be pressed into service lugging in some heavy purchase from the garage. I never minded. It was nice to contribute, to feel as though I had a place with an understood set of expectations. Plus, it was flattering. It’s no secret that I’m fat, and working out either to lose weight or to gain muscle has always held about the same level of appeal as plucking a cactus clean of needles with my teeth. With Audra’s father out of the picture (and collecting alimony from her mother), it felt satisfying to play the role of the big, strong, helpful guy.

The opportunity came with a price, however, and it was for this reason that I would often take my leave shortly after Audra’s mother made her entrance. As soon as I had finished whatever task Mrs. Facinelli had on tap for me, the next line in the script was always the same.

“Would you like to stay for dinner?”

I would always hope to avoid the confrontation, but I had studied my lines well. I’d worked it out. People feel a social obligation to offer guests food, I had observed, but this certainly didn’t mean they wanted to follow through. Sitcoms had provided excellent educational aids: Danny Tanner throwing a good-natured eye-roll when his daughter’s boyfriend raided the fridge, Turk gnawing at a comically oversized block of cheese and responding to Elliot’s disgusted stare by reluctantly waving the blocking her direction and asking, “¿Queso?” This wasn’t the rule, of course; undoubtedly, there were times in which an offer was made in earnest. Faced with the ambiguity, however, I had determined that the safest course of action was to assume the offer was merely meant to be polite and, therefore, to decline. In this way, I couldn’t possibly overstep an invisible bright red line.

Now, commands were a different story, deserving of their own place in the algorithm. “Here, have a cookie” is not a question asked in the hope that it be answered in the negative; it is an expression of the intended outcome. In these cases, the intent is clear: for whatever arcane reason, Person A explicitly wants Person B to consume the comestible in question. (My theory was that Person A intended to receive commendation for his or her superb taste or culinary abilities.) Another exception was the planned shared meal or the party; in these cases, stipulations are made up front and are understood by all such that the hosts cannot suddenly find themselves without food that they had intended for themselves. There was an asterisk here, though: recognizing that I was horizontally gifted, it was crucial that I eat only the minimum required to suggest that I did not actively dislike the dish being served.

In Mrs. Facinelli’s case, I followed the flow chart faithfully. “No, thanks,” I recited as I set down the fifty-pound box of kitty litter.

“Are you sure?” Mrs. Facinelli persisted. “I feel bad, expecting you to do all this work for me for nothing. It’s dinner time anyway, and you’re already here.”

A wrinkle in the page of the script, perhaps, but nothing I couldn’t handle. Earlier in the relationship, I had acquiesced to one meal, spending the ordeal carefully monitoring to make sure I was not served too much, nor did I consume too much. It had been exhausting. Plus, she’d given me a clue tonight: it was dinnertime. I decoded the message: “It’s our dinnertime and you being here would make it awkward for us to eat without giving you any. Thus, while you are welcome to return, please leave now.”

“No, really, I’m okay,” I tossed back, marching confidently to safety across the perilously narrow beam. “But thank you. I really should head home anyway.”

“All right,” Mrs. Facinelli sighed in response. “Thanks for the help.” I smiled and turned to the door, another crisis averted.

A few months later, when Audra broke up with me, she recited a manifesto detailing the numerous defects in my behavior and character she had observed. Among the top five: “You always make my mom feel insulted because you won’t eat her food.”

It is undoubtedly uncommon for the target of an intervention to call for it himself, but I clearly needed help. Nearly a decade had passed, and I was no closer to a satisfactory procedure for identifying offers of food made out of obligation from offers of food which themselves were obligations. This quirk of mine was hardly a secret anymore—I had made a habit of poking fun at it. In the same breath, I’d often ask the opinions of friends, usually a hair too casually. Replies were less than helpful. If a person didn’t want an offer accepted, they shouldn’t have made it in the first place, one person had told me. If they’ve got more than one serving, you’re supposed to accept, but if they only have enough for themselves, you should decline, suggested another. Most were surprised by the question in the first place. One-on-one wasn’t cutting it.

So, one crisp autumn evening, I ambushed my roommates.

“Okay, so how in the hell do you tell when someone is genuinely offering food?” I asked the group.

A beat passed before Zak hazarded a reply. “I guess,” he started, hesitating. “I guess you could listen to their tone? Like, if they’re hesitant, then maybe don’t take it? I mean, people buy food intending to share it, right?”

Eddie, our international correspondent, chimed in next through his thick African accent. “In Nigeria, if you say you do not want my food, it means you are my enemy,” he said before lobbing a guffaw.

Beeman decided he would simply solve the problem. “Well, when I offer you food, you’d better take it, ‘cause I don’t do it that often and I might change my mind.” Great. Thanks.

“Really,” I interjected. “Isn’t it safer to decline?”

“Why not just accept if you want it?” Zak asked. “It’s just food.”

The cloying aroma hangs heavy, clouding my thinking. I stare at the container of cupcakes in front of me. It’s okay—I’ve drilled for this. No need to panic. I think back to my training.

Three pastries remain in the container, next to nine empty spaces.

We are not in Nigeria.

Her tone was neutral.

Rachel is definitely not Beeman.

It…should be safe.

They’re just cupcakes; it’s not like beluga caviar. I’d happily let Rachel eat food I’ve bought for myself. It’s not as though these are the last cupcakes ever to be produced. It doesn’t matter what she thinks—even if she’s just offering to be polite, accepting certainly won’t drive her to hate me for the rest of forever. I can make sure to bring something the next time I come over.

I close my eyes as I screw up the courage. I can accept the mini cupcake, so dainty with its frosting in fall colors atop artisanally processed chocolate. I can manage to make the right choice without offending anyone. I can be normal.

My eyes open. I meet her gaze.

What if she wanted the cupcake?

“No, thanks,” I say. “I’m good.”

Rachel looks confused for a moment. Then she shrugs. “Suit yourself,” she says, turning to her roommates. “Anyone else?”

About the Poet

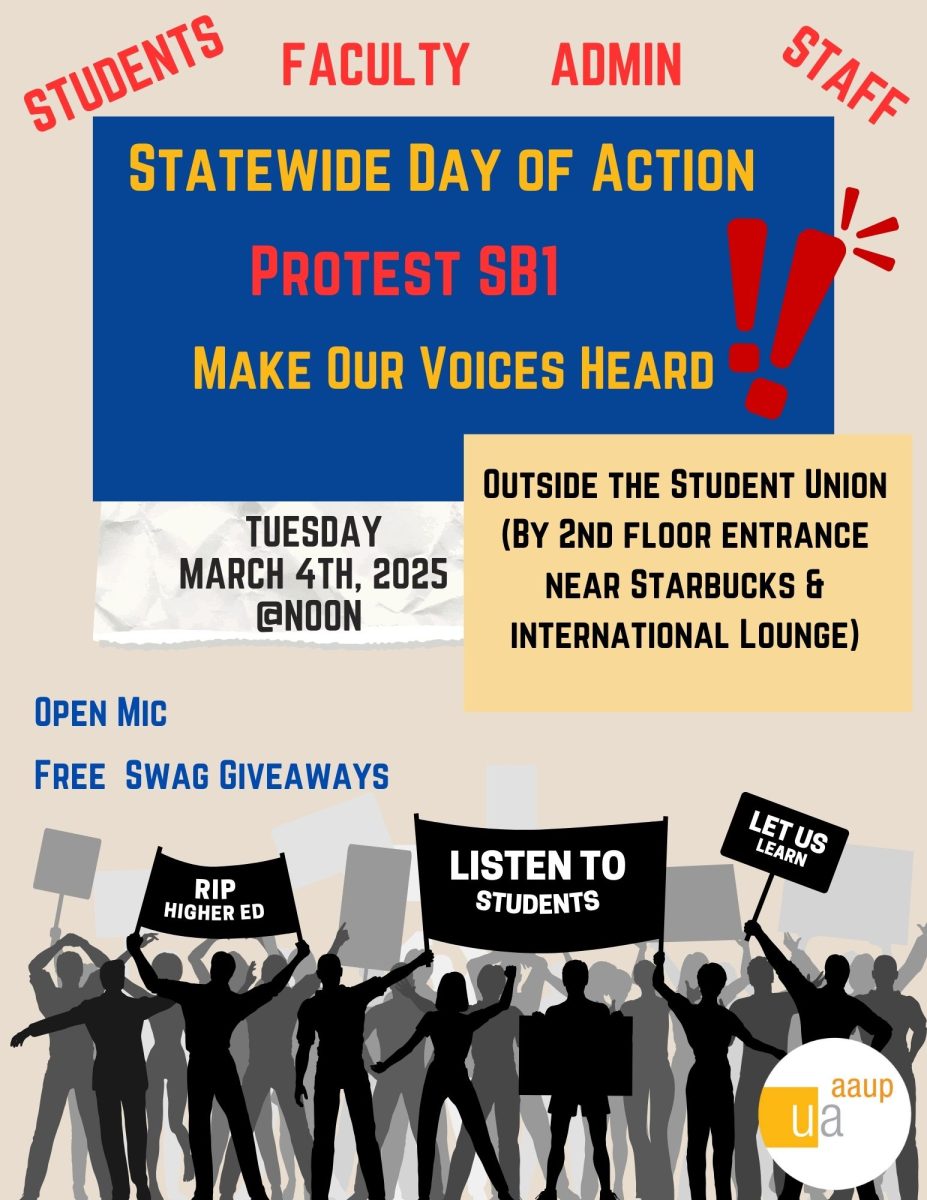

Will Carney is a senior at The University of Akron. He enjoys exploring the union of creative writing with his major in psychology, playing with the individual differences in perception and reasoning that divide and define us. He hopes to begin graduate school in research psychology next fall.

Aimee Trunko • Nov 7, 2018 at 9:04 AM

That was excellent and really captured all of the hamster wheel machinations of the anxiety-ridden mind. I really enjoyed reading it. Keep up the good work!