Kyle Steiner

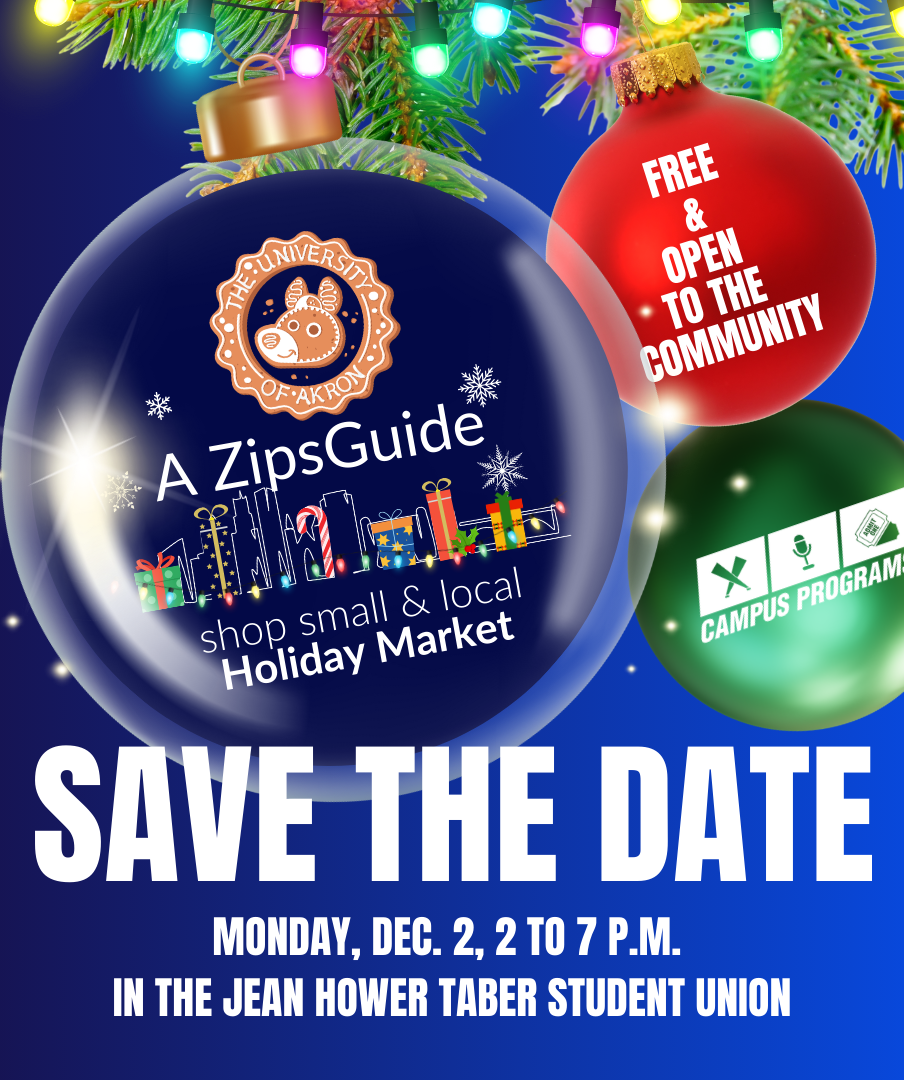

A group of concerned youths huddled around a television that hangs from the wall in the Student Union at The University of Akron on Feb. 14.

They pensively observed the screen as news about the former Los Angeles police officer, Christopher Dorner, who allegedly murdered three people, slowly began to trickle in.

According to MSN News, the 33-year-old former police officer’s body was recovered Wednesday afternoon from a burning shack in the mountains above Los Angeles, where it is reported that he made his final stand against what he believed to be a racist police department.

According to the Huffington Post, after being fired from the LAPD, Christopher Dorner released a manifesto where he said, “The department has not changed since the Rampart and Rodney King days. It has gotten worse.”

Seemingly fed up with the system, Christopher Dorner vowed revenge against the police officers who were associated with his dismissal from the police force.

“You’re going to see what a whistle-blower can do when you take everything from him, especially his name,” Dorner said in his manifesto.

Dorner began targeting LAPD officers and their families. This sparked a major manhunt over the next week for the alleged cop killer which eventually culminated into a million dollar reward offer from the LAPD for information on Dorner’s whereabouts.

According to MSN News, Dorner’s deeds began to receive a massive following in mainstream media, social networking sites including Facebook, and various message boards across the web. Many people who commented seemed to sympathize with Dorner’s situation, and some have even managed to label him a vigilante, claiming they support what he’s done.

However, Christopher Dorner is not the first man in history to attempt to eliminate an allegedly racist institution through the use of violence. In fact, Dorner’s story bears a striking resemblance to that of John Brown, a man who has a memorial built in his honor near the Akron Zoo.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, John Brown, best known for being a militant abolitionist, led an attack in 1856 on a group of people who openly supported slavery in Kansas, which resulted in five deaths.

Brown was arrested after attempting a second raid on a federal armory in West Virginia, which was ultimately unsuccessful, and led to Brown being tried as a murderer and executed on Dec. 2, 1859.

According to akronhistory.org, in 1910, the Akron German-American Alliance erected a memorial for John Brown on a hill where Brown herded sheep for Colonel Simon Perkins. After decades of being in disrepair and subject to multiple acts of vandalism, the monument was fenced in by the Akron Zoo, which became essentially responsible for regulating public access to it.

“When the memorial was open to the general public, it got damaged,” said Akron Zoo Public Relations representative David Barnhart. “The area got enclosed back in 2000, so now it is only accessible by appointment.”

In light of recent events, several professors at The University of Akron were willing to give their perspectives on a comparison between John Brown and Christopher Dorner, and reopen the discussion about Brown’s legacy and impact on American History.

“Both individuals, John Brown and Christopher Dorner, believe the ends justify the means,” Bill Lyons, director for conflict management and professor of political science at UA, said.

Lyons commented on the violent methods that Brown and Dorner used to try to achieve their political objectives.

“If you are trying to work for racial justice, the way you do it is more important than the outcome,” Lyons said. “The only real impact we have is how we act now. The whole point of a democracy is that we respect individual rights.”

History professor Dr. Walter Hixson also shared his viewpoint on the

two individuals.

“It’s an insult to John Brown to link him to Dorner,” Hixson said. “The one thing that links them is their willingness for violence. Most people are going to view Dorner as insane.”

Insane was the exact term that history professor Dr. Kevin Kern used to describe how some people view John Brown.

“A lot of people argue that he was crazy,” Kern said. “In a democratic society, it comes down to the people and the people dislike violence.”

Kern said that Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an anti-slavery book written by Harriet Beecher Stowe, did more to change people’s minds about slavery than John Brown, saying that the only difference between Brown and Dorner is that Dorner worked as a lone wolf while Brown was part of a movement.

Kern said that Brown’s actions did not help his cause and violence does not usually yield good results.

“John Brown’s actions only hardened the southerners’ desire to fight back,” Kern said. “It took decades, but things did change from nonviolent means.”

Jon Miller, an American literature professor at UA, said that he believes Brown and the memorial erected in his honor are an important part of American history.

“There’s no doubt that since his execution in 1859, John Brown has been considered a great hero by many Americans,” Miller said. “His story involves so many of the most intense and enduring disagreements among Americans about civil rights, government, war and religion.”

Miller said that there has been a lot of debate about whether or not Brown was a terrorist in the current sense of the word, and the conclusion of the research is no.

“People who study Brown in depth tend to come away with mixed but generally sympathetic feelings about him and his actions,” Miller said. “But really, it depends on how you define the word ‘terrorist.’”

History professor Dr. Lesley Gordon said that “hero” is not an appropriate word to describe Brown, saying that at that time, Brown’s abolitionist group was seen as radical and that Brown wasn’t popular until after his death.

“However, I do think that what John Brown did had to happen in order for things to change,” Gordon said. “For example, the Quakers, who were pacifists and the first organized abolitionists in the United States, presented a petition for banning slavery, but were turned away.”

Only time will tell whether or not future scholars will discuss Christopher Dorner’s last stand the same way they currently discuss John Brown’s historical raid.

“As is always the case in history, what people think is true is always more important than what is true,” Kern said.