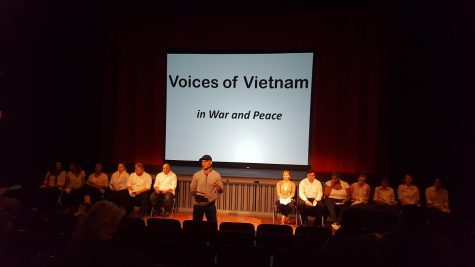

Students retell voices of Vietnam

Seniors Lia Pietrolungo and Chad Weaver retell the conversation between a young Vietnamese student and their grandmother about the war in Vietnam.

November 9, 2016

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. is a black wall listing the names of the 58,200 Americans who died in the Vietnam War. This wall is 150 yards long. If we made a monument listing the three million Vietnamese who died in that same war, that wall would be four-and-a-half miles long.

This is how University of Akron senior English students introduced a play they performed yesterday in Kolbe Hall’s Daum Theater. The play, called “Voices of Vietnam,” retells the true stories of some of the Vietnamese who lived through the conflict.

The students put on the play as part of UA English professor Patrick Chura’s senior seminar. Chura wrote “Voices of Vietnam” over the summer of 2016 when he visited Vietnam to teach a Vietnam War literature course to students at Ho Chi Minh City Open University. His five-week stay was funded by a grant from the Fulbright Specialists Program.

As part of the course, Chura’s Vietnamese students interviewed their parents and grandparents about their experiences during the “War of American Aggression,” as they call it. At first, Chura says many of his students – and their parents – were hesitant to speak out about the war because freedom of speech is limited under the Vietnamese government.

“I felt like I had to translate the dignity and respect that [my students] showed to conduct these interviews in a country that does not fully recognize the right to free speech,” Chura told the audience during yesterday’s show.

After some effort, Chura said, his Vietnamese students managed to collect a series of first-person narratives that they then translated into English. Chura edited and scripted them into six scenes. He created a narrative that involves current U.S.-Vietnam relations to create a dialogue between the different characters.

He did not add much, however: around 95 percent of the play is taken verbatim from the people interviewed.

Chura’s class in Ho Chi Minh City performed the play on June 2.

Chura includes a section in the play for the Vietnamese students to include their own voices. With the government pushing one version of the war in their history books and many older generation Vietnamese refusing to speak, younger generation Vietnamese urge their elders to begin telling them real stories about the war.

To complement the performance in Akron, Chura invited Vietnam veteran Henry McNeil and May 4 Kent State shooting survivor Dean Kahler to add their voices.

The UA students introduced each speaker after reciting the words of their Vietnamese peers.

During his Vietnam tour, McNeil said that the Viet Cong did not differentiate him, an African-American, from other soldiers. The Americans were all, simply, the enemy. He says it was sometimes difficult to tell if a Vietnamese person was an enemy or a friend.

He agrees with many of those interviewed in Vietnam: war is hell, no matter which side you’re on.

A few months into his tour, McNeil realized he wasn’t getting paid. He decided to investigate, and ended up, to the confusion of him and his colonel, getting out of the field. A few days later, while McNeil was working elsewhere, all of the men he served alongside were killed in battle.

Next was Dean Kahler, who was wounded during the Vietnam War protests and subsequent shootings on May 4, 1970 at Kent State University. Before Kahler retold the events of that night, he said he needed to give a little background.

Kalher’s father was a veteran who saw combat during World War II and then joined occupation forces during the Korean War. Kahler, however, was raised a pacifist. When he wasn’t drafted during the Vietnam War, Kahler, who was eligible to serve in a civilian capacity, said he had been disappointed that he could not serve his country as his father had done.

Kahler arrived at Kent State University in the spring semester of 1970. At the time, students were protesting the war in Vietnam, and Kahler says he wanted to see a demonstration. One of his professors, however, warned him against going since the National Guard had been called in. “Don’t get close to those people,” his professor said. “They have rifles.”

At the demonstration, the National Guard faced off with the students. Protesters started throwing rocks; soldiers threw tear gas. Kahler says he stood and watched the soldiers huddle, march up a hill, and raise their rifles.

“I knew immediately that they were going to fire,” he said. “There was nowhere to hide.”

The soldiers fired on the protestors. Kahler was hit in the spinal cord, paralyzing him below the waist.

Today, Kahler is still coming to terms with the shootings. “It’s hard for me to forgive them for shooting college students with the same rifle my father carried,” he told the audience.

After the play, many of the students called the play, and Chura’s class, “eye-opening.”

“This — performing this play and being in the senior seminar — has been a way for us to go back and trace a dark part in our nation’s history and also grow more empathy,” senior Lia Pietrolungo said.

Other students said that the play helped them better relate and understand the issues that still divide Vietnam. “When you have to present someone else’s story, someone else’s feelings… there [is] a seriousness to it,” Micah Palitto said.

After the performance, Chura thanked both sets of students and the guest speakers for attending. The next step, he says, is to make the public more aware of these voices.

English professor Patrick Chura (seen above) scripted “Voices of Vietnam” from the interviews his Vietnamese students collected over the summer.