Letter to the Editor: Unfinished

May 1, 2023

As Buchtelite advisor, you will rarely hear my voice in the paper. The paper is here to amplify student voices. On Sunday, April 30, I set out to meet a student editor at “Unfinished,” The University of Akron Choral program’s last concert of the school year. I had offered to capture video so they could focus on the concert. Click here to see the edited video, highlighting moments of the performance.

Unfortunately, the editor was unable to attend at the last minute. I stayed focused, because the student voices I was concerned with amplifying in that moment were the ones standing up on risers preparing to sing. Those voices are the reason for this unsolicited letter to my student editors.

As I sat capturing video, I couldn’t help building a review in my head. After 15 years singing in the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus and others, I’ve performed the Mozart Requiem many times.

Then again, I wasn’t there to see the Requiem.

A little over a week ago, I attended a panel put on by the UA Center for Conflict Management on the social justice aspects of the Jayland Walker verdict. I saw my former student Izzy Anderson who told me about “The Seven Last Words of The Unarmed.”

She spoke the name of the piece as if I should know it, but I didn’t. She spoke it as a response to me asking how she was processing the verdict as a student of color. The piece, she told me, set the seven last words of unarmed Black men killed by authority figures to music.

About “The Seven Last Words of the Unarmed”

I wanted to know more, so I researched the piece and composer. Joel Thompson premiered the piece in 2015. According to an interview he gave at the time, Thompson used the liturgical format of Haydn’s “Seven Last Words of Christ” to humanize the men whose last words he featured, and, as he put it, “to reckon with my identity as a Black man in this country in relation to this specific scourge of police brutality.”

In addition to his use of the Seven Last Words, famously used in reference to the last words of Christ, the composer makes use of musical symbolism, most notably in weaving a secular tune from the Renaissance, “L’homme arme doibt on doubter,” which translates as “the armed man must be feared,” throughout the movements.

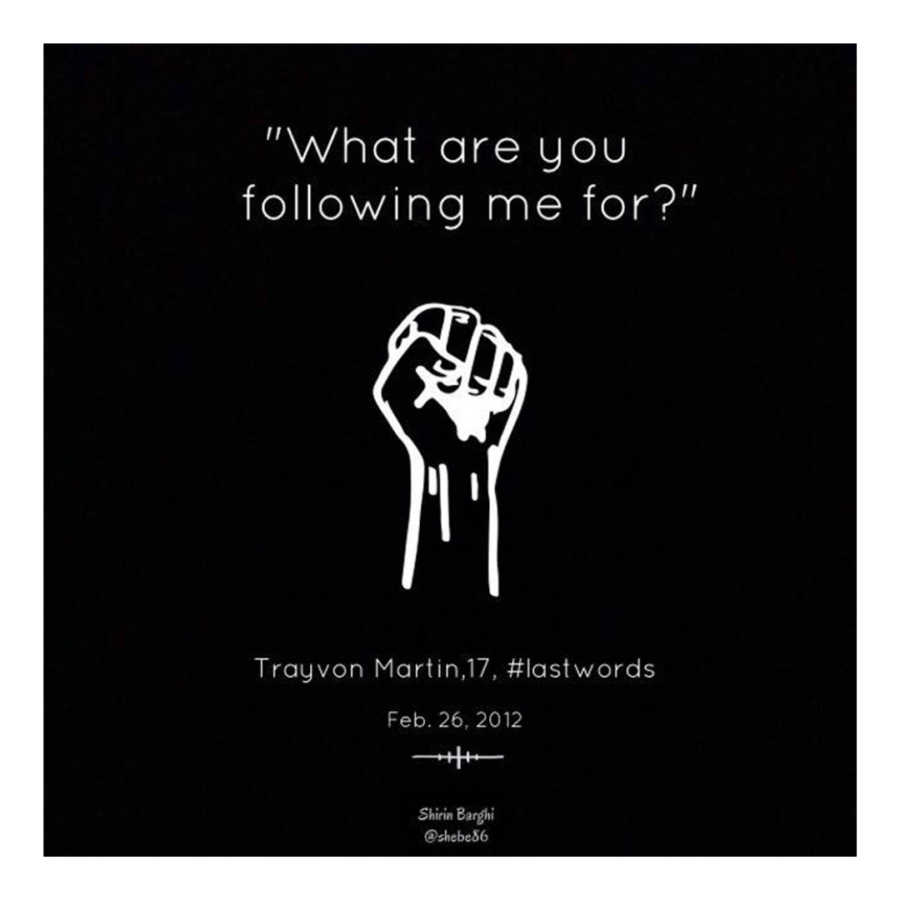

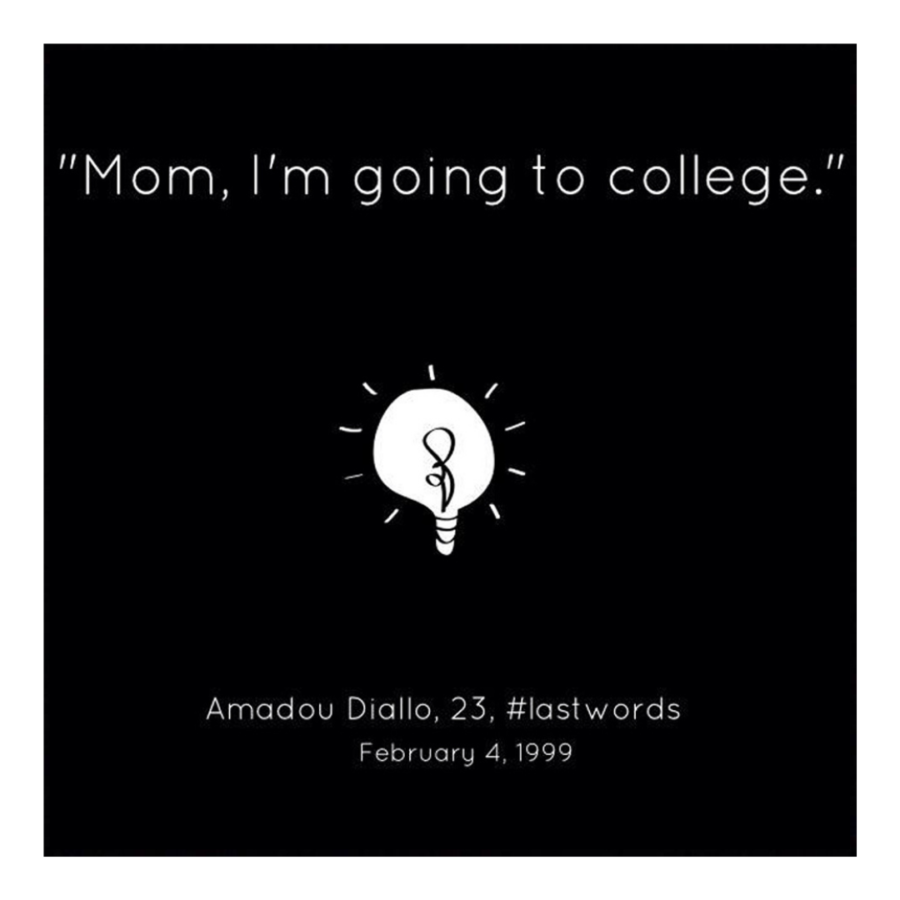

Thompson was also inspired by the art of Shirin Barghi, an Iranian journalist who created the #lastwords project. According to her website, the “series was started in 2014 to capture the #LastWords of Black victims of police violence, and a reminder of the devastating toll that American racism, and state violence takes on black families & communities.”

The website Thompson built for ‘The Seven Last Words of the Unarmed’ explains that though more than 100 Black men have been killed while unarmed in the last decade, these seven were selected as their last words align best with the form of the composition.

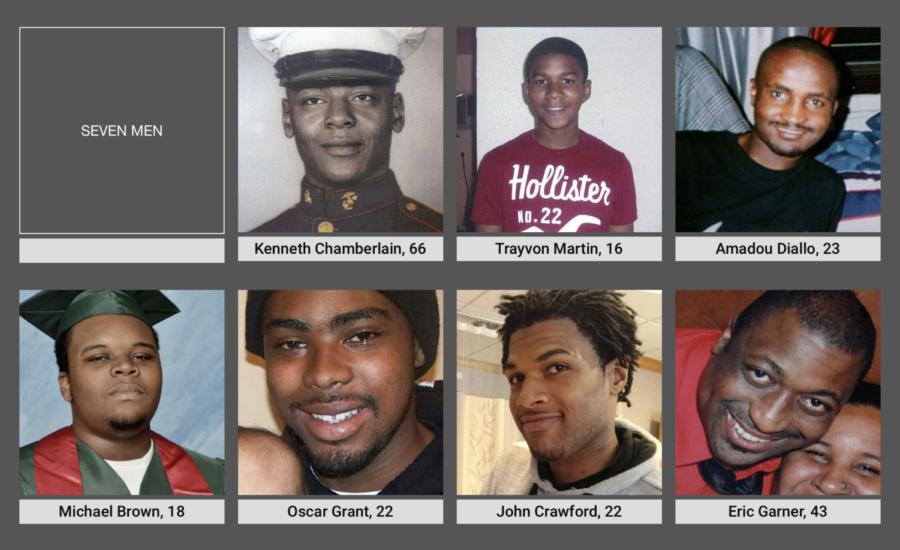

The movements are named for the seven unarmed Black men that Thompson selected. These include I. Kenneth Chamberlain, II. Trayvon Martin, III. Amadou Diallo, IV. Michael Brown, V. Oscar Grant III, VI. John Crawford, VII. Eric Garner.

In another interview, Thompson discussed having students perform the work. “Providing a safe place for students to express and process issues that affect us all can be very rewarding and act as another vehicle for bringing change to our world,” he said.

Student members of the glee club who premiered the piece were concerned about what they saw as the overly political statement it was making. In the end, the members and the audience found resonance in the central theme of loss and found the experience a positive one.

Conductor and director of the Choral Program at UA, Dr. Marie Bucoy-Calavan did not program the work to align with the grand jury decision or with any specific event. She saw it, instead, as a needed opportunity for her students and for concertgoers to think about the ripple effect in how these unfinished lives impact all of us.

“As a person of color at Akron, which is a predominantly white space, the opportunity for this work to be performed and heard does mean a lot to me,” Isabella Anderson, 23-year-old student from Parma, Ohio, said. When it comes to the politics, she agrees wholeheartedly with Thompson and Bucoy-Calavan.

“I don’t believe it to be political,” she said. “These are human lives.”

According to Anderson, preparations for the concert sparked productive conversation among UA choral students as they processed recent events concerning the Jayland Walker verdict.

While the concert didn’t take a stance on the results of the trial or the implicit social justice issues, the students appreciated having an outlet to think more deeply on what has happened in their community and how it affects them.

The Pre-Concert Lecture

At 3 p.m., I sat and began to record. First, Bucoy-Calavan stood up and talked about “Unfinished,” in relation to both the Mozart Requiem and The Seven Last Words. She supplied much of the musical context for The Seven Last Words that I had learned in my research and outlined how the death of Mozart left his requiem unfinished.

Then, Reverend Raymond Greene Jr. walked slowly up to the podium. For a pastor and community organizer, his initial presence was unassuming, even a bit quiet. His words, though, were anything but. They cut deeply to the core of what it is to be a Black man in 2023 and connected that experience directly with being a Black man in America in 1623 or 1923.

Whenever I hear the term “strange fruit,” I immediately feel the hair on the back of my neck raise. I can remember the first time I heard it and imagined some sort of exotic or tropical cultivar, only to learn that it was a euphemism for the bodies of Black men hanging from trees.

Reverend Greene reminded the audience that not only were Black men lynched, but lynchings were seen as entertainment for the whole family, including women and children. “They were a warning to other Black men,” said Greene, “comply or die.”

In a poignant section of his address, he changed hats from organizer to pastor and evoked the gospel’s descriptions of the life and death of Jesus. He was also hung from a tree after throwing out the money changers in the temple, battling the capitalism that he saw as blasphemy in his father’s house.

Throughout his talk, he illustrated ways that society and what he referred to as corporate greed have created and profited from fear.

“The fear of Black men is not about White folks,” he said.

“It’s not the white folks who created it,” Rev. Greene said. “It’s about evil. Evil that is driven and fueled by a capitalistic system.”

Reverend Greene concluded by saying that he is hopeful. Hopeful that “the world will put aside their ill-advised fears of the Black man as the boogeyman, and see us for the beautiful, creative, disciplined, loving, protective human beings that we are.”

By the end of his talk, his voice had risen to a firm, impassioned tone. Two of his closing comments stuck with me.

“We must understand that no man can be authentically human when he prevents others from being that very same thing,” he said. “There are a lot of inauthentic people out there.”

And then, Reverend Greene’s last words.

“If Black men matter, can we matter when we’re alive, and not just when we’re dead?”

The Performance

Bucoy-Calavan dedicated the opening piece to the Black men who spoke those last words and to Jayland Walker. The large space at Westminster Presbyterian church was filled; audience members even ventured up to the choir loft for seats.

The tenors and basses opened the performance with the chanted words of Kenneth Chamberlain: “officers, why do you have your guns out?” This first movement with close harmonies grew to a climax, then ended darkly with all the singers intoning “why” on an unresolved and dissonant chord that reminded me of the meditative singing of Buddhist Monks. The piano repeated a rhythmic motif, but suddenly dampened, cutting off the sound abruptly, leaving the movement feeling unfinished.

The second movement featured the words of Trayvon Martin: “What are you following me for?” It opened with an agitated rhythm in the strings and conveyed the palpable fear and confusion that a person might feel if they were being followed by an unknown person. The program noted it was also meant to sonically capture the paranoia of the Black experience. I found myself thinking, is it paranoia? The singers performed the harmonically and rhythmically challenging material with accuracy and urgency, finishing with a surprised shout.

The most consonant, the third movement was also the most haunting and heart wrenching for me. The last words Amadou Diallo is believed to have uttered were in a voicemail he left for his mother: “Mom, I’m going to college.”

Tenor Jeff Boggs delivered the words in a moving solo with a bit of emotional tremble in his voice. As a mother, I imagined what Diallo’s mother must have felt like playing back that voicemail after his death. I imagined my seven-year-old saying those words.

The last two movements were played attacca, or, without pause. Michael Brown says, “I don’t have a gun, stop shooting.” What appeared to be a group of traditionally young, college-aged singers performed with maturity and depth beyond their years. The rage they imbued into the word “stop” as it was emphasized and repeated conveyed clear meaning to the listener.

The final movement used the tenor and basses’ bodies as percussion. They pounded their palms into their chests over their heart and spoke the words of Oscar Grant III, “You shot me. You shot me!” It was only after the performance that I read the program note explaining that the shouts were aleatoric, meaning at random. The singers had performed difficult rhythms and harmonies so deftly throughout the piece, I was impressed with their accuracy and commitment during the movement. It did not seem random.

The singers began to hum L’homme arme doibt on doubter in a style that the program described as that of a spiritual, with the instruments playing the part of the steady then destabilizing then silenced heart monitor.

I’m sure with more reflection I will look back on this letter/review/reaction and wish I had picked out other nuances and symbolism in the piece. It was a painful listen that made my stomach churn, but a necessary one.

Art humanizes. Art helps us see through other people’s eyes. It allows us to walk a mile or a lifetime in their shoes. I am not a Black mother, and my sons are not Black men, but by the end of the piece, I had connected their real loss with what my loss would be in their shoes.

The convincing and committed performances by the singers helped me make that connection. Bravo to them for being brave enough to sing this and for keeping their own emotional responses in check enough to sing it well.

Mozart’s Requiem

As I was preparing to write up a review of the performance of the Mozart Requiem, I tried to remember a time I had listened to the full piece in its entirety. It’s possible that I have never heard the work performed in concert, only performed it.

The University of Akron Chamber and Concert Choirs gave a stunning performance. I was so taken by the beauty and agility of their singing that I forgot I was listening to students perform. I was immersed in the sound and in watching them experience the majesty of the work themselves, some I’m sure for the first time.

This time the requiem had a different gravity, perhaps because it was following “You shot me. You shot me!” Or perhaps it was seeing (unintentionally) the photos of Jayland Walker’s broken body after being shot 46 times in the days leading up to the concert.

When the singers reached the Rex tremendae, I had my first ‘goosebump moment’ when the sopranos and altos sang the weeping text ‘salva me.’ In contrast with the booming Rex tremendae, the ‘salva me’ connected so directly to the words of the unarmed men and the remarks of Reverend Greene. Save me, the voices implored.

There would be many more moments where my breath would catch in my throat and my skin would tingle during the requiem, mostly driven by the beautiful contrasts elicited from the singers by Bucoy-Calavan.

The formidable quartet of soloists included soprano Dr. Alexandria Hanhold; mezzo-soprano Kimberly Lauritsen; tenor Brian Skoog; and Bass-Baritone Dr. Frank Ward.

The soloists emerged from the texture of the orchestra and soared above it in gorgeous balance. Standouts for me were the mezzo-soprano and the tenor. The mezzo’s tone was rich and luxurious in the lower range and powerful and beautiful in the mid and upper ranges. The tenor was both warm and clear in the Liber scriptus, and his annunciation was crisp throughout. In the Benedictus, I got tingles from the soprano as her lyrical tone and gorgeous vibrato reached higher into her range.

The combined choruses gave a powerful, moving performance. The fugue in the Kyrie was clean and churning, the singers moving agilely and accurately through the melismatic passages. The chorus sopranos and altos delivered some of the most breathtaking moments of the requiem in their pianissimo passages, which were perfectly in tune.

The orchestra should also be mentioned. It’s hard to believe this group hasn’t been playing together regularly under Bucoy-Calavan’s baton. The combined forces of UA faculty, students, alumni and area high school students blended seamlessly. They were sensitive, responsive and perfectly balanced to support and showcase the singers.

The Lacrymosa, one of the well-known movements, was achingly beautiful, though I craved more finality, weight and climax in the opening phrase. While listening, I recalled a time when my choral director had us begin on the first day of rehearsal by singing the opening bars of the Lacrymosa and then stopping after the eighth bar. He looked at us for impact in the silence and told us that those eight bars were the last in the piece that Mozart himself had even sketched.

Today, listening to the rest, it is beautiful music. It was so clear, though, listening from the audience, that Mozart had left the room. The piece was left unfinished, and his student tried to complete it, but without even a sketch from Mozart, the music lost his prodigious magic.

Then, in the final two movements, Süssmayr repurposes Mozart’s musical material from the Lacrymosa and the Kyrie, and suddenly Mozart steps back in, as if he refused to allow his work to end in the hands of someone else.

We, as a community, need to refuse to let the lives and legacies of the seven unarmed men and the hundred others killed in the last decade end in the hands of someone else.

We need to pick up where they left off and remember their lives and their loss by seeking justice and progress. Their final words should echo in the actions of every member of the community to realize Reverend Green’s hope, that Black lives will matter while they are still alive.

“Unfinished” was presented in partnership with UA faculty and alumni, along with area high school students and The David and Orlene Makinson Memorial Endowed Concert Series.

Robert j • Jun 7, 2024 at 11:52 AM

Okay I’m not the voice for anyone but I am a voice that speaks the true nature of the educational department on recreational therapy for students on campus in campus or around campus at Akron University whatever the whole point of this this comment is to let the people who are in charge of Akron university’s student activities the students are lacking in activities to keep them motivated in recreational therapies that are positively enforced given that the university in and its location are on the edge of the hood which brings in a whole different element in that is an element that conflicts the interest of education and mostly the female and then the male students in that order and I I’m only stating this because I asked a student working a job at a drive-thru which was a female I asked her if she could tell me one of the things that she liked the most about Akron you and going to school and working a job and then one thing that she didn’t like the most with that same situation and these are the the topics that were brought up in her statement and she really wish that there were more student activities and that they could limit the traffic flow on the streets of Akron University to allow to change the flow of traffic so that the incoming traffic came from a different direction and be outgoing traffic also going in a different direction so that it would limit the access to the roads coming into and going out of the Akron University area not just the campus but fundamentally there are not enough activities mainly not enough activities in or planned for the students who are attending the school

Julie Cajigas • Sep 13, 2024 at 6:23 PM

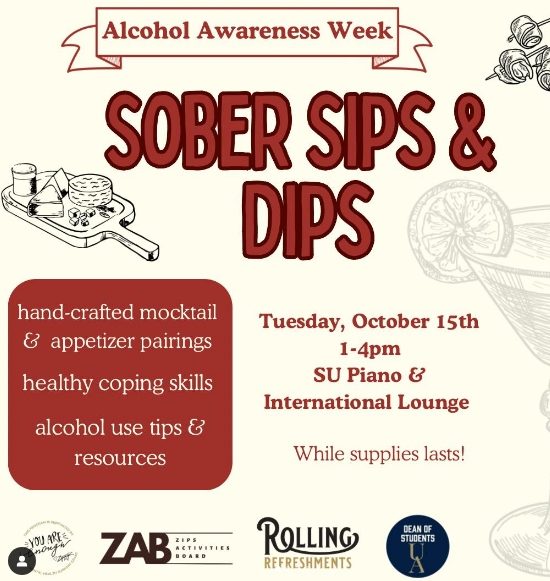

Hello Robert, I am the author of this editorial and the advisor for The Buchtelite, Julie Cajigas. There are over 300 student organizations and clubs on campus, most of which hold events and meetings regularly, as well as an extremely active department of student life, greek fraternities and sororities, tons of athletic events, a recreation center with swimming and work out equipment, there is an active office that plans mental health and wellness based activities, a career services office with various career-building activities, and an active study abroad program. Then, there is this student newspaper, which can’t manage to get more than a handful of students who are interested in coming out and writing. There are so many activities going on that we could never report on all of them or even a fraction of them. I have a hard time imagining how anyone could complain about not enough activities available.

I’m a bit confused about the traffic comment. I commute into Akron every day and rarely run into a traffic issue. So I can’t comment on that.

If you run into her again, I would encourage her to attend RooFest or another one of the massive tabling events. There is a student tailgate this weekend where many student organizations will be represented and there will be games and food trucks (for example).

Kacey Yates Gable • May 3, 2023 at 8:59 AM

Thank you for sharing this review. Just wanted to ask that you edit the caption on the picture that says Westminster Presbyterian Church is located at 1205 W Exchange St, as it is actually located at 1250 W Exchange St. We hope to offer more concerts to the community and encourage anyone to join us for worship in our open and inclusive sanctuary.

Julie Cajigas • May 3, 2023 at 4:08 PM

Thank you, we made that correction.